Text

Human Experiences around Bananas

By: Luis A. Gutierrez

Our personal experiences as consumers in a global economy could not be more different from those in the production sector. In this case, I am referring to production as the cultivation, collection, and distribution of crops. One of those crops is bananas; they are part of our daily diet as one of the cheapest and most reliable fruits in the supermarket. Artists utilize and celebrate the banana in many forms, from songs like Harry Belafonte’s Star-O and Andy Warhol’s paintings to the infamous piece Comedian by Maurizio Cattelan. While other artists and writers have chosen to depict or elaborate on the damaging effects bananas have on those who live where they grow. Examples of this include Diego Rivera’s mural Gloriosa Victoria, Fernando Botero’s painting Masacre en Colombia, the Nobel Prize-winning novel, Cien años de Soledad (One Hundred Years of Solitude) by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, as well as the investigative work of Peter Chapman in his book Bananas. In this essay, I am referring to experiences as a set of physical and psychological conditions that shape an individual’s life.

On December 6th, 1928, thousands of banana plantation workers gathered together after weeks of protest against the United Fruit Company (UFC) in Cienaga, Colombia. They awaited a train that would bring the Magdalena Governor and other UFC representatives to end the strike by accepting the petitions of twenty-five thousand workers represented by Unión Sindical de Trabajadores del Magdalena (Magdalena workers Union). But instead, the train brought General Cortez Vargas and his troops, who declared the strike unlawful, demanding the strikers to disperse and obey the shelter in place mandate. Giving the crowd only a few minutes to break up the gathering, the General read a message stating that anybody who refused to leave would be shot. The soldiers, armed with pistols and rifles, prepared to engage the crowd where women and children were also present.

According to first-hand eyewitnesses, General Vargaz shouted, “one minute left to disperse,” answering back, a man yelled, “you can keep that minute, assholes” (1). It is essential to highlight the frustration and disappointment of the strikers. It was not the first nor the last protest against the United Fruit Company, who continued to violate Colombian national workers protection laws without any government intervention. Local officials like Cienaga’s mayor Victor Manuel Fuentes did support the demands made by the workers. Consequently strikes followed in 1910, 1918, 1927, 1928, and 1934. Some of the demands were as basic as collective health insurance, accident protection in the workplace, paid time-off on Sundays, weekly salaries, termination of vouchers as a form of payments, and a pay increase for those who earn the least (2). La Unión Sindical de Trabajadores del Magdalena sent a copy of these petitions to the United Fruit Company, the President, and the Ministry of Industry of Colombia. (3) Not only was the UFC systematically breaking the law, but it had also created a new way to maximize its revenue by monopolizing the chain of production. The company paid workers with vouchers used in exchange for goods at the convenience stores owned and operated by the same company. The laborers had to buy everything in the stores: from food and appliances to tools required for work. According to the book, Bananas by Peter Chapman, “In the realm of big knives, United Fruit was the largest machete buyer in the world. Each labourer, mozos, ‘peasants,’ had to have one purchased from the company store (4).”

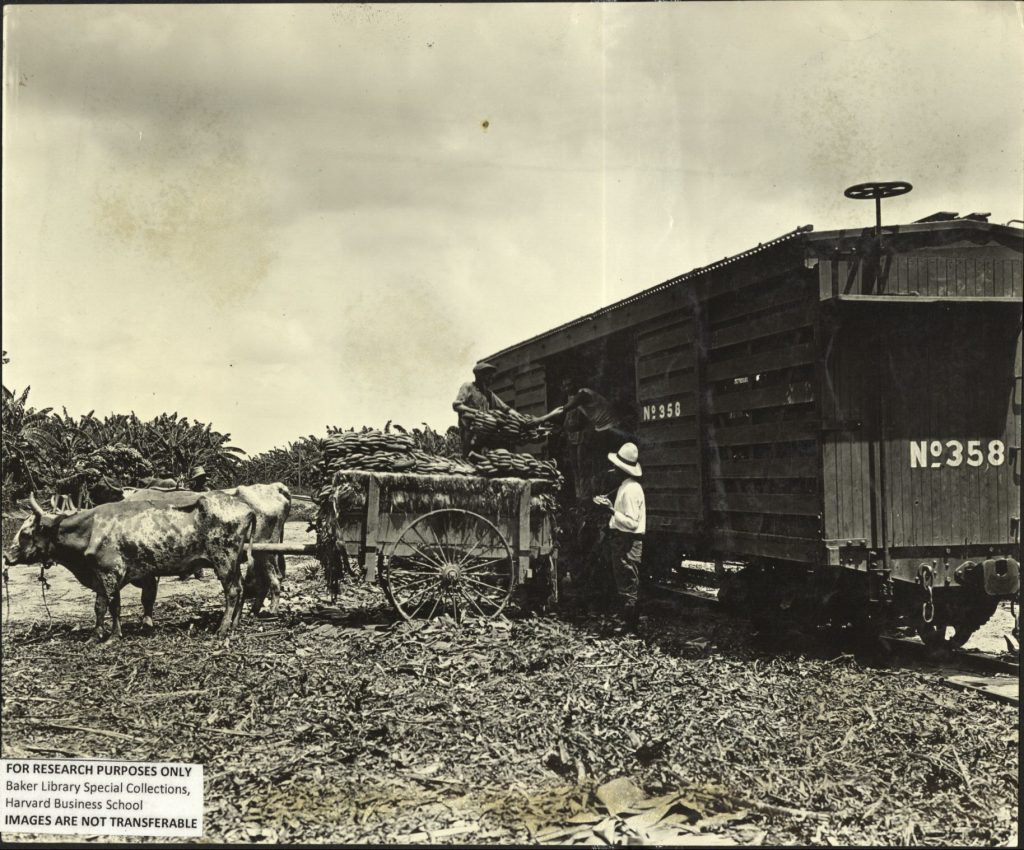

The man who shouted, “you can keep that minute, assholes,” could not have imagined what was to come. A scene usually only reserved for the most horrific and violent of movies occured on that early morning. General Vargaz ordered his men to open fire on the crowd of protesters. Men, women, and children alike screamed and ran for their lives (5). This event became known as La Matanza de las Bananeras (The Banana Massacre). Newspapers cited as little as nine to one hundred deaths but the true number of victims is unknown (6). There was no official record kept by the Government except for a critical piece of evidence presented by a telegram from Jefferson Caffery, U.S. Ambassador to Colombia (1928–1933), to the Secretary of State. In the telegram dated February 8th, 1929, Caffery writes: “I have the Honor to report that the Bogota representative of the United Fruit Company told me yesterday that the total number of strikers killed by the Colombian military exceeded one thousand (7).” Fernando Botero’s painting Masacre en Colombia serves as a visual narrative to describe the violence used against thousands of civilians on December 6th, 1928, in the United Fruit Company’s name.

During the 20th century, the company continued its expansion through Latin America to places like Ecuador, Panama, Costa Rica, Honduras, Guatemala, and the Caribbean Islands, starting a new revolution in the food sector. From the first banana boat whichdocked in the U.S. in 1871, bananas have not stopped coming to our supermarkets. At one point, the UFC extended across millions of acres or 12,000 square kilometers (8). It drove the competition out of the market by owning the land, controlling the railroad systems in many countries, and the ships that transported the fruit. Its broad power throughout the region was used to form coups and overthrow governments whenever it felt threatened. One of the most notorious examples is the overthrow of democratically elected Guatemalan President Jacobo Arbenz by the Central Intelligence Agency. The CIA conducted operation PBSuccess with the excuse of eliminating communism in the region. (8) President Arbenz created the Agrarian Reform of 1952 to bring more equality to Guatemalan citizens. This reform mandated the company to sell some of their grounds at reported value. The UFC had acquired the land by taking advantage of the corruption in previous governments. This motivated the company to lobby the United States Congress to act and approve the CIA operation and overthrow the government of Arbenz, putting an end to the policies that would affect the company’s operations in that country. The effect of the UFC’s lobbying power in Washington would continue to influence U.S. international policies towards Latin America, changing and shaping local governments for generations to come, affecting the experiences of those who lived where bananas grow. In the mural Gloriosa Victoria by the painter Diego Rivera, we can make out essential faces that were part of Operation PBSuccess as well as the suffering and frustration of the Guatemalan people.

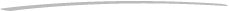

While most industries in today’s world have been totally or partially automatized, physical labor is still required when collecting the banana bunches. In the song Star-O by Harry Belafonte, we can hear references to the hardships laborers have endured while working in the plantations, “Lift Six-foot, Seven-foot, Eight-foot bunches.” Other significant issues laborers continue to face are the high temperatures and humidity levels in areas where the crops grow, let alone the massive amounts of fertilizers use, causing cancer and other diseases. Only a few kinds of bananas are commercialized globally, meaning that most plants are derived from the same genetic pool, making them extremely vulnerable to diseases.

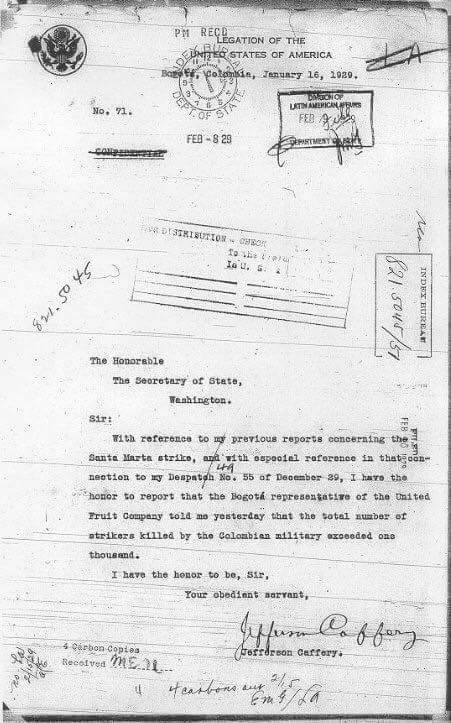

On the other hand, we have the consumer’s experience represented in Andy Warhol’s banana paintings, designed to be the album cover for The Velvet Underground band. The cover’s first editions intended for the fans to peel off the banana’s yellow skin revealing a pink fruit underneath. Just as we peel off the United Fruit Company’s facade as one who brought jobs and structural advances to Latin America while satisfying and influencing the consumers’ expectations. Another example is the piece Comedian, a banana taped to a wall, by Maurizio Cattelan. Its meaning can take many forms depending on the viewer, highlighting the importance of the viewer’s experience as part of a work of art that can transcend its physical qualities, as mentioned by John Dewey in his collection of essays presented as a book called Art as an Experience. Warhol’s and Cattelan’s pieces are different from those of the previous artists mentioned as they did not intend to expose the sufferings of the people behind the production of bananas. It is important to note that their personal experiences and motives to use bananas as inspiration are not less valuable or less important. They merely represent different human experiences influenced by each individual’s socio-political status and the place in which we are born.

Growing up listening to the injustices committed against laborers in Colombia and reading One Hundred Years of Solitude in which Marquez, inspired by his experiences growing up in UFC times, writes a remarkable but tragic story full of injustices and death, encouraged me to investigate more about La Matanza de las Bananeras and learn about the banana industry’s dark beginnings. As a response, I created Entre Sombras, a group of mixed-media paintings bringing together a hybrid of investigation and physical engagement. The visual information taken from archives, like the photographs of plantation workers, their families, and surroundings, serves as a foundation upon which this series has been built. The images used are digitally abstracted and distorted. Through the use of different materials, my work becomes a record of physical traces manipulated, torn apart, and then brought together in layers to reference collective amnesia and the loss of information through time. I am interested in gathering information to gain a deeper insight into historical events while understanding that history is represented in books, physical objects, and individual experiences.

Researching the banana industry has helped me recognize the differences between my personal experiences as a Colombian native living in the United States and those who work and live where bananas grow. As John Dewey wrote, “The career and destiny of a living being are bound up with its interchanges with its environment, not externally but in the most intimate way.” This close relationship between the artists and their experiences allows for the existence of such diverse and rich forms of art. By actively looking at art, we can learn from history, see the world through others’ experiences, and even forget about our own reality. The United Fruit Company ultimately influenced and continues to shape the political and social landscape of the so-called “Banana Republics.” They have created two polar ways of experiencing bananas; as producers and consumers.

Bibliographic References:

-González, Ana María. “La Noche De La Vergüenza Nacional: Así Fue La Masacre De Las Bananeras.” El Tiempo, El Tiempo, 6 Dec. 2018, www.eltiempo.com/colombia/otras-ciudades/asi-fue-la-masacre-de-las-bananeras-la-noche-de-la-verguenza-nacional-302386.

-Aguilera Peña, M. (2010) «Mauricio Archila Neira y Leidy Jazmín Torres Cendales, editores. Bananeras. Huelga y Masacre. 80 años.», Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de la Cultura, 37(1), pp. 289-292. Disponible en: https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/achsc/article/view/18384 (Accedido: 18febrero2021)

-Redes, Editor. “La Masacre De Las Bananeras: ‘No Ha Pasado Nada, Ni Está Pasando Ni Pasará Nunca’ – Colombia Informa Recordando.” Colombia Informa, 25 Sept. 2019, www.colombiainforma.info/5-y-6-de-diciembre-la-masacre-de-las-bananeras-la-matanza-que-si-ocurrio/.

-Chapman, Peter. Bananas: How the United Fruit Company Shaped the World (101) Canongate, 2008.

-Kurtz-phelan, Daniel. “Big Fruit.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 2 Mar. 2008, www.nytimes.com/2008/03/02/books/review/Kurtz-Phelan-t.html.

-Núñez, Óscar Alarcón. “La Masacre De Las Bananeras: ¿Cuántos Muertos Hubo?” Semana.com Últimas Noticias De Colombia y El Mundo, 29 Aug. 2020, www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/masacre-de-las-bananeras-90-anos-de-la-tragedia-que-marco-a-colombia/592107/.

-“Records of the U.S. Department of State Relating to Internal Affairs of. . . . Microfilm.” The SHAFR Guide Online, doi:10.1163/2468-1733_shafr_sim140020007.